Blog written by Catie Gould and Ron Davis, originally posted here by Sightline Institute and is reposted here with permission.

Parking reform unlocks more homes and great neighborhoods, while cutting red tape and excess asphalt, sprawl, and pollution.

Cities, towns, and jurisdictions around the world are adopting a powerful reform that accelerates homebuilding, eliminates red tape for small businesses, reduces pollution and sprawl, revitalizes downtowns, and streamlines permitting—at zero cost to the taxpayer.

That reform? Eliminating parking mandates—local governments’ arcane and unfounded requirements that every new home or business come with an arbitrary, pre-determined number of parking spaces. These requirements hamstring local builders and business owners, drive up rents and home costs, and write sprawl into law. It’s time to return these decisions to the people investing in their communities, whether a homeowner, homebuilder, or entrepreneur, who are best positioned to know how many parking spaces they need for their dream to succeed.

In Washington state specifically, the legislature is considering a bill to do just that: the Parking Reform and Modernization, SB 5184 (companion bill HB 1299).

SB 5184 would cap excessive parking mandates both for residential and commercial construction, restoring people’s ability to decide for themselves how many parking spots they need, instead of the ratios some city planner wrote down back in, say, 1963. It would also give full parking flexibility to project types that need it most, like repurposing existing buildings for cafes or apartments and building more middle housing and affordable housing, daycares, and more. (Read the full Sightline Institute explainer of the Parking Reform and Modernization Act here.)

Communities considering parking reform for themselves can look to the many other jurisdictions that have already enacted it for a view into what they can expect in a world with fewer parking mandates, including:

More homes, in all shapes and sizes, from backyard cottages and duplexes to apartment buildings and affordable housing

More great neighborhoods, with creative reuse and preservation of historic buildings, smart sharing agreements for existing parking, and even conversions of parking lots to new communities of homes and shops

Less unneeded asphalt and the pollution, deadly “heat islands,” and long-lasting sprawl that come with it, paving over nearby farmland and open spaces

Less red tape and costly delays for builders and city staff alike

More nimble adaptation to modern parking-lite conveniences like online shopping, remote work options, and ride-hail apps

More money in local budgets for everything from firefighting to libraries, after-school programs to parks, and other community priorities

Sound too good to be true? Read on to learn more about the power of parking reform.

1. More homes of all shapes and sizes

More middle housing, like backyard cottages and fourplexes

Even one parking spot can render a backyard cottage impossible to build. A study out of Kent, Washington, for example, found that 85 percent of residential properties didn’t have room to add an additional parking space that local rules mandated owners to have if they wanted to build a backyard cottage.

In 2023, Washington legalized accessory dwellings along with other middle housing options like fourplexes. But unless the property is near a major transit stop, homeowners still have to meet local parking mandates, whether or not they want or need the parking.

Since neighboring Oregon implemented its sweeping parking reforms in 2023, middle housing is sprouting up that would not have been possible under prior parking rules. One project, Grant Street Grow Homes, in Eugene, Oregon, was able to add four backyard homes without demolishing the existing primary house only because no off-street parking was required. The new homes are now selling for $96,000 each to qualified buyers.

The Grant Street Grow Homes are far from outliers in the Beaver State. In Portland, 79 percent of homes permitted since the 2021 middle housing reform kicked in opted not to add off-street parking, including the vast majority of fourplexes. This means a lot more of the modest-sized homes Portlanders want and need could come on the market and make the most of the space available to build. Washington’s SB 5184’s full parking flexibility for residences under 1,200 square feet would free typical middle housing homes from the mandates that would otherwise prevent them from ever existing.

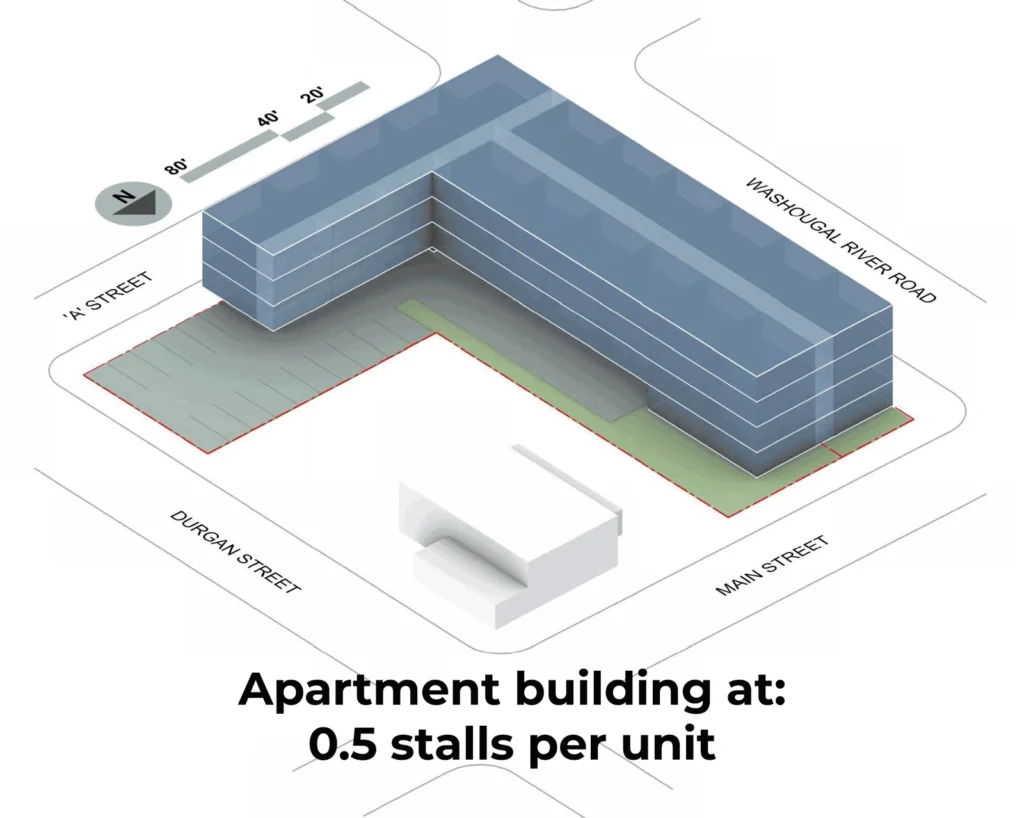

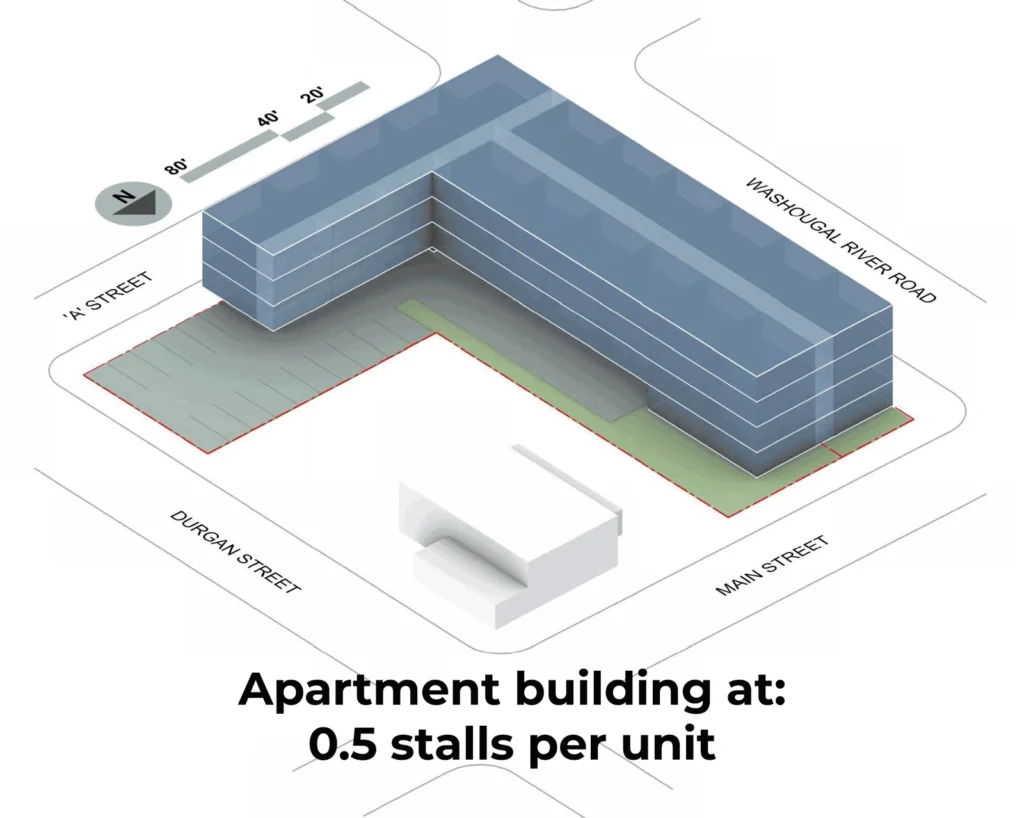

More homes fit into apartment buildings

Apartment buildings are an important ingredient for cities to add the variety of sizes and price points residents need. And while most people might think that local height or density limits dictate the number of homes permitted in a new apartment building, it’s frequently arbitrary parking mandates.

For example, a parking lot with capacity for 10 vehicles could legally support an apartment building of 20 homes in Washington’s capital city of Olympia, which requires 0.5 spaces per multifamily home. That same 10-spot parking lot in Seattle-adjacent Mercer Island, though, which requires 2 parking spots apiece, would only support a building of 5 homes. Both cities have an apartment building with a parking lot for 10 vehicles; but one city is getting far more bang for its apartment-building buck thanks to a lower parking-space-to-home ratio.

Once untethered from pre-determined parking ratios, apartment builders frequently choose to build more homes than they could have otherwise. From Beaverton, Oregon, to Bellingham, Washington, when cities stop micro-managing parking counts, their communities get more housing. Indeed, studies of multifamily housing built post-parking reform in Seattle and in Buffalo, New York, both found that the majority of new homes would have been illegal under the prior parking minimums, even though most new buildings still included some parking.

Lower home costs and rents

Depending on the cost of land and the type of parking structure, a single parking space can cost anywhere from $5,000 to $60,000. The costs of a recent Sound Transit1 parking garage’s spaces ballooned to $200,000 each. Those costs get rolled into the cost of every project and product they’re attached to.

For residential projects, they can add hundreds of dollars to someone’s rent. Even when landlords charge a nominal fee for parking spots, they still lose an average of $246 per month per apartment, according to a Sightline study of 23 multifamily Seattle-area buildings. Those costs get passed down to all tenants, whether or not they own a car they need to store.

That study is now ten years old, too, meaning that figure is surely higher today. Another analysis from that same time period that averaged costs across numerous US cities found one parking spot added a monthly average of $225 to the cost of rent.

More subsidized affordable housing

It’s no surprise that Washington’s greatest shortage of homes is of those that are affordable to people at the lowest income levels. This demographic—including seniors and people with disabilities—is also less likely to own a car.

Affordable housing providers are often on the front lines of the fight against overbuilding parking. Too often, they experience the steep costs and delays of having to request zoning variances so they can avoid wasting money and space on parking their residents don’t need. Uncertainty around how much parking a given city or town might ultimately require can delay the construction of affordable homes. Excessive parking mandates also give leverage to activists bent on keeping affordable housing out of their neighborhoods.

Bonus: Parking reform unlocks way more new homes than other (also good) reforms

An analysis from Colorado showed that compared with the status quo, reducing mandates to 0.5 parking spaces per home near transit, and 1 space per home everywhere else would result in 41 percent more homes becoming financially feasible to build. That one policy change made a bigger difference for housing than legalizing backyard cottages (+22 percent) and allowing larger buildings near transit (+13 percent) combined.

The increase in potential homes was primarily driven by already-feasible multifamily buildings increasing the number of apartments beyond what existing parking ratios would have allowed.

2. More great neighborhoods

More beautiful neighborhoods

Think of the most desirable neighborhood of your city, the one you would love to live in if you could afford it. What do you see? Maybe narrow streets, large trees that shade the sidewalk, old houses with lots of historic character, maybe with a coffee shop on the corner.

What don’t you envision? Large parking lots.

Often our most sought-after real estate is attractive and valuable because it was built before parking mandates existed. In typical Washington cities, much of the building stock from the 1950s or earlier would not have enough parking to meet today’s requirements. Eliminating parking mandates allows new buildings to better match the character of older buildings and preserve the type of neighborhoods that many people already love.

More creative reuse of historic buildings

Vacant buildings can come back to life when owners get to decide for themselves if the site’s existing parking is sufficient. That was the primary reason that Fayetteville, Arkansas, removed parking minimums for all commercial buildings. And it worked.

“The buildings I had identified as being perpetually and perhaps permanently unusable were very quickly purchased, redeveloped, and are in use right now,” city planner Quin Thompson told Sightline. Legislation like Washington’s Parking Reform and Modernization Act, SB 5184, would similarly allow all existing buildings to find new lives without being hamstrung by parking mandates.

Smart sharing arrangements to better use existing parking lots

There are far more efficient and cheaper ways to provide customers and tenants with the parking they need than requiring every building to have its own private parking lot. A business owner with excess parking can lease out their extra spaces to a business next door.

For example, commercial-to-residential building conversions in downtown Hartford, Connecticut, use nearby parking garages to offer off-street parking for tenants who want it (and spare that cost for tenants who don’t). Since many office workers have gone remote, there is a glut of such parking available.

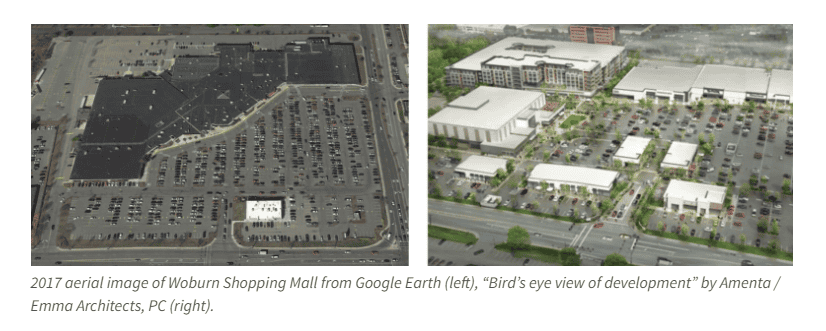

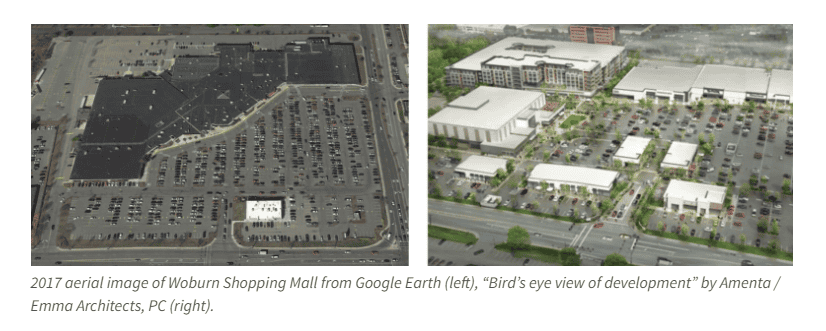

More conversions of parking lots we don’t need to buildings we do

Without parking mandates, space occupied by empty asphalt can be repurposed into much-needed new homes, services, or businesses. Seabrook, New Hampshire, was able to add a regional bus station in the parking lot of a former big box store after the town removed parking mandates. And Woburn, Massachusetts, gave an old mall property new life when it swapped its sea of parking for a community made up of apartments, shops, and yes, still some parking (before and after aerial shots below).

Want to transform an old strip mall into a walkable neighborhood with businesses and housing mixed together? Parking reform is one of the necessary ingredients to make it work. In Olympia, Washington, the Capital Mall is one such site that the city would love to transform into a real neighborhood. But the mall is in fact defined as “underparked,” meaning it is hundreds of parking spaces short of meeting what current zoning rules would mandate. A penstroke change to those rules could open up all sorts of possibilities for local entrepreneurs and homebuilders.

3. Less unneeded asphalt, sprawl, and pollution

Less overbuilding of parking, above car ownership levels

Cities and counties require more parking than many people need. A Sightline study of jurisdictions across Washington state found that while one of every four homeowner households owns one or no cars, detached homes are nearly universally required (91 percent of jurisdictions) to have two parking spaces each.

Excessive parking mandates are even more out of line with the needs of renters. 58 percent of Washington renter households own one or no cars, but even for a studio apartment—in which tenants forgo a bedroom to save money on rent—most cities still mandate that they come with parking. In fact, six out of ten jurisdictions require more than one parking space for a studio, and two out of ten require two spots apiece. These rules mandate overbuilding parking for the majority of renters, and that costly-to-build parking, in turn, needlessly raises their rent.

Less of parking lots’ long-lasting sprawl and pollution

Allowing buildings to locate nearer to one another, rather than across a sea of parking or busy roads to accommodate parking mandates, means less creep into neighboring farmland and nature. The space consumed by mandated parking spreads buildings apart, which increases sprawl, stormwater runoff, traffic, pollution, and commute times. Sprawl and runoff from tailpipe emissions and car tire deterioration also stress watersheds, the ecosystem services they provide, and the wildlife they shelter.

What’s more, once built, these parking lots don’t go away overnight. Unless redeveloped, they lock in these impacts for decades, as well as the less tangible normalizing for local residents to expect to drive everywhere they need to go. Even in urban environments like San Francisco, research applying randomized housing lotteries has shown that more parking results in increased car ownership and more driving.

Less “heat island” effect in our already warming communities

Parking reform would mean that we stop mandating “heat islands” in our communities. Large asphalt parking lots soak up the sun’s energy during the day and release it back at night. During heatwaves, which are becoming more common as climate change warms the planet, high overnight temperatures become fatal, as people are unable to recover from heat stress. Planting trees can help some, but reducing pavement in the first place gets at the root of the problem. (Note, too: Trees don’t thrive in parking lots where their roots are in soil that is compacted and hot.)

One analysis of a heat island in Portland, Oregon, found that it was concentrated around a commercial area that had 3 parking spots for every 1,000 square feet of commercial space. At that ratio, parking lots are roughly the same size as the buildings they serve. (Three parking spots per 1,000 square feet is a common parking minimum for businesses in Washington state.)

Reduced parking mandates can allow these large parking lots to fill in with buildings that break up the pavement and provide shade, while also providing new shops and services a community might need.

4. Less red tape for local businesses and governments alike

Parking needs are site- and project-specific

Parking is always a hyperlocal question, particular to a project’s site, context, and use. The people investing in their communities, whether a homeowner, homebuilder, or entrepreneur, are best positioned to know how many spaces they need for their dream to succeed.

Dana Christiansen was surprised when she tried to open a new daycare in the “daycare desert”-designated Clark County, Washington, that she would have to build 32 parking spaces for the number of families she hoped to serve—way more than what she wanted. Her existing daycare in Vancouver, Washington, ran fine with just 8. Her lived experience couldn’t compete with local regulations, though, and when the property could only fit 29 parking spaces, she was forced to walk away from the project.

Mountains of parking paperwork don’t serve anyone

When they don’t have to negotiate over parking spaces or apply for a zoning variance, builders save time and money—and so do local governments. Development projects that fall short of required parking can sometimes win approval but only after conquering a headache-inducing mountain of paperwork and sometimes committee and public meetings, too.

That was the case for the owners of a brewery in Anchorage, Alaska. The previous owner had added a dining room to the building without adding the parking that local rules required, so the city threatened to close the addition. To defend their business, the new owners had to conduct a two-week parking study to prove what they already knew: the parking lot rarely got full. The city eventually approved the parking reduction, but everyone lost time and money over six measly parking spaces.

Parking mandates are an outdated idea, widely adopted in the 1950s or 1960s. That was before the internet, online shopping, work-from-home arrangements, or ride-hail apps. Demand for parking changes, but zoning codes get stuck in the past.

Even superstores like Walmart are building less parking than they used to due to the rise of online shopping and regularly ask local governments to build less parking than code requires. As trends continue in ways foreseen and not, it makes most sense to leave the parking decisions to those closest to their customers’ changing needs and preferences.

It’s a win-win for local budgets

When parking reform makes possible much-needed home construction and supports area businesses, it’s a boost to local economies, and at no expense to taxpayers. In fact, local governments are likely to see property tax revenue increase as more homes and businesses become possible thanks to commonsense parking reforms. An analysis of parking lots in Hartford, Connecticut, estimated that the city was losing out on $1,200 a year of potential property taxes per off-street parking space downtown.

And yes, we’ll still have plenty of parking…

Parking will still get built. Sorry to disappoint the de-pavers of the world, but the overbuilt parking we have today isn’t disappearing tomorrow, and as communities grow and add more homes and businesses, they also add some parking, even if it’s less than it would have been with parking mandates.

Cities rarely continue to count parking spots once they aren’t required to, but growing Edmonton, Alberta, which officially repealed parking minimums in June 2020, still added 20,000 parking spaces through 2020 and 2021. Even in transit-rich Seattle, after builders received full flexibility in some parts of the city in 2012, they still voluntarily built more than 26,000 new parking spaces for new housing projects.

That said, as lifting parking mandates allows for more flexible, real-time, and project-specific decisions over time—all happening alongside other changes like more public transit deployment, safe-streets measures that spur more people walking, rolling, and biking, and continued technological developments that can reduce the need for car travel—we needn’t anticipate a world that only ever builds more parking. We just need to let our cities and towns, and the thousands of local builders and entrepreneurs who call those places home, decide what’s right for them as they shape their communities’ future.

We’ll just have more of the good stuff, too

The benefits of parking reform are many: more of the homes we need, more of the neighborhoods we love, less excess pavement, pollution, and sprawl, and less red tape. It means letting business owners and builders, homeowners and renters, decide the amount of parking that’s right for them and find options that suit their needs and budgets. It means getting smart with the plenty of parking we’ve already built into our main streets and neighborhoods rather than prescribing even more unsightly asphalt as our communities grow.

In short, eliminating parking mandates doesn’t make parking disappear, but it does provide more choice about how much to provide and make better use of the parking we already have. Parking spaces will still get built, but so will daycares, homes, and ice cream shops, too.

About the Authors

Catie Gould (pronounced “Go͝old”) is a senior transportation researcher for Sightline Institute, specializing in parking policy.

Ron Davis is a contributor with Sightline Institute helping to build coalitions for affordable, equitable, sustainable cities and towns in Washington state.

About Sightline

Sightline Institute is an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit think tank providing leading original analysis of democracy, forests, energy, and housing policy in the Pacific Northwest, Alaska, British Columbia, and beyond.